Guest Columns: The Ranting Room (Bruce Bethke) (December 13, 2008) http://rantingroom.blogspot.com/2008/12/guest-column-michael-shaara-wishing-for.html

Guest Column

"Old friend Guy Stewart regularly blogs at Possibly Irritating Essays. A while back I gave him an unusual book and a challenge. Herewith, the result."He never won any awards with us. No Hugo, no Nebula (oh, that’s right, he’d stopped writing SF by 1966 and gone on to pen seventy stories for people who read those silly magazines like Redbook, Cosmopolitan, Playboy, and The Saturday Evening Post), no Locus Poll (oops, those didn’t start until 1971, and Shaara was long gone by then); he left us almost nothing to remind us that we’d had a great writer doing his apprenticeship among us, the SF community. Somewhere around 1954 he wrote a story that Galaxy, F&SF, and Astounding rejected out of hand after publishing seven other stories of his; Shaara himself thought, “…this may be the best I’ve ever done.” But we didn’t want it. Published finally, grudgingly, in Fantastic Universe in 1957, Shaara had already started moving toward people who enjoyed what he was writing.

That story, “Death of a Hunter”, wasn’t the best he could do. Twenty years later, the world saw the publication of his Civil War novel, The Killer Angels.

An intimate novel of the Battle of Gettysburg in the style of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage, Angels became his best. Winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1975, the award came as a stunning surprise because the book had been a commercial flop — and then went on to become a full-length feature film after his death in 1988, and has been required reading for more military organizations than you can shake a stick at ever since.

The SF world lost Michael Shaara because in part, the editor at Galaxy thought his readers wouldn’t like “Death of a Hunter”. They wouldn’t like it because he thought it was, “too serious, too gloomy.” Of course, the SF of the time tended toward the positive salvation of humanity through the application of technology. Shaara’s work didn’t flow in that vein — it wasn’t about glittering machines and conquering the planets, the stars, and the galaxies. His work was about people and their responses to the forces in their lives. That phase of popular SF didn’t arrive for another twenty years.

Admittedly, Shaara also wrote better after 20 years of practice. Compare these two descriptions of the alien:

Admittedly, Shaara also wrote better after 20 years of practice. Compare these two descriptions of the alien:

“It was a great black lump on a platform. The platform had legs, and the thing was plodding methodically upon a path which would bring it past him. It had come down from the rise and was rounding the gorge when Dylan saw it. It did not see him. If he had not ducked quickly and brought up his gun, the monkey would not have seen him either, but there was no time for regret. The monkey was several yards to the right of the lump on the platform when he heard it start running; he had to look up this time, and saw it leaping toward him over the snow.” (p. 32, “Soldier Boy”, 1954)

“To be alien and alone among white lords and glittering machines, uprooted by brute force and threat of death from the familiar earth of what he did not even know was Africa, to be shipped in the black stinking darkness across an ocean he had not dreamed existed, forced then to work on alien soil, strange beyond belief, by men with guns whose words he could not even comprehend. What could the black man know of what was happening? Chamberlain tried to imagine it. He had seen ignorance, but this was more than that. What could this man know of borders and state’s rights and the Constitution and Dred Scott? What…” (p. 180, The Killer Angels, 1974)Both passages are one hundred and eleven words long, but it is clear that Shaara had come into his own by the time he wrote Angels. The prose vibrates like a quartet’s string bass played in an intimate curtained chamber, while “Soldier Boy” twangs like a banjo in a clapboard dance hall.

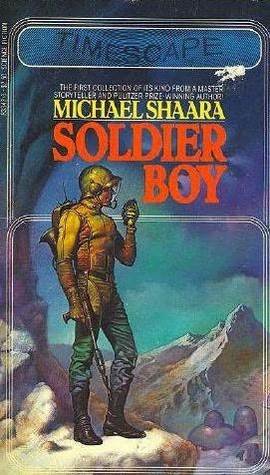

Is there anything we could have done to keep him with us — perhaps allowing the growth of an early Mary Doria Russel, or Stanislaw Lem? Unlikely. SF hadn’t matured enough by then to admit to literary aspirations. Shaara himself alludes to this in the afterword of Soldier Boy, the only collection of his science fiction ever printed. He says, “Very little I wrote has ever moved me so much as being with Neilson when he killed those two in the mountains. I felt for the first time in my writing life, that maybe I was growing up, and maybe I’d done something truly worth doing…”

Fifty-eight years later, Shaara’s work has stood the test of time, as The Killer Angels enjoys consistent sales and continues to illuminate one of the bloodiest battles in American history. As good as it is, though, I cannot help but wonder what Michael Shaara might have given the SF community, had we encouraged him to explore the darker reaches of humanity’s battle with technology.

No comments:

Post a Comment